Abstract

A belt conveyor system represents a foundational technology in mechanical material handling, engineered to transport goods, raw materials, and bulk solids with high efficiency over various distances. This analysis examines the system's core principles, structural components, and operational dynamics. It details the interplay between the conveyor belt, drive mechanism, pulleys, and supporting idlers, which collectively enable continuous and controlled movement. The system's functionality is predicated on the principles of friction and tension, which are managed through sophisticated engineering to ensure reliability and longevity. Different types of belt conveyors, such as flat, troughed, and modular designs, are explored in the context of their specific industrial applications. The adaptability of the belt conveyor system allows for its widespread use in sectors ranging from mining and logistics to manufacturing and agriculture. By providing a continuous transport solution, these systems significantly enhance productivity, reduce manual labor, and streamline complex operational workflows, making them an indispensable asset in modern industry.

Key Takeaways

- A belt conveyor system automates the transport of materials, boosting operational efficiency.

- Key components include the belt, drive, pulleys, and idlers, all working in unison.

- Proper belt tension and alignment are fundamental for reliable system performance.

- Select a conveyor type based on material characteristics and the required path.

- Regular maintenance prevents downtime and extends the equipment's service life.

- Modern systems integrate sensors for predictive maintenance and improved safety.

- Understanding your specific application is the first step to choosing the right belt conveyor system.

Table of Contents

- Unpacking the Belt Conveyor System: A Foundational Overview

- The Anatomy of a Belt Conveyor: Core Components and Their Functions

- The Physics and Engineering Behind Belt Conveyor Operation

- A Typology of Belt Conveyor Systems: Matching the Machine to the Mission

- Belt Conveyor Systems in Action: A 2025 Look at 5 Key Industries

- Selecting the Right Belt Conveyor System: A Strategic Decision Framework

- The Future of Belt Conveyors: Innovations and Trends for 2025 and Beyond

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Conclusion

- References

Unpacking the Belt Conveyor System: A Foundational Overview

To truly grasp the significance of the belt conveyor system in our interconnected global economy, we must first look beyond its apparent simplicity. One might see a looping band of material moving items from one point to another and perceive a straightforward mechanism. Yet, within that perception lies a rich history of innovation and a complex interplay of engineering principles that have been refined over centuries. Thinking of it merely as a moving belt is akin to describing a library as just a room with books; it misses the entire structure, purpose, and profound impact of the collection. Let's begin our exploration by establishing a solid conceptual foundation.

The Core Principle: Continuous Motion and Material Transport

At its heart, a belt conveyor system is a mechanical apparatus that employs a continuous loop of material—the conveyor belt—stretched across two or more pulleys. One or more of these pulleys are powered, causing the belt and the items resting upon it to move forward. This principle of continuous motion is what makes the belt conveyor system so remarkably efficient. Unlike batch-based transport methods, such as forklifts or carts, which involve discrete start-and-stop cycles of loading, moving, and unloading, a conveyor offers an uninterrupted flow.

Imagine a line of people passing buckets of water from a well to a fire. This is a form of serial, continuous transport. Now, imagine replacing that line of people with a single, long trough of moving water. The efficiency gain is monumental. This is the conceptual leap that the belt conveyor system provides for industries. It transforms material handling from a series of individual tasks into a single, cohesive, and automated process. The system's capacity is not limited by the speed of a single vehicle or worker but is instead defined by the belt's width, its speed, and the characteristics of the material it carries.

A Historical Perspective: From Early Innovations to Modern Automation

The lineage of the belt conveyor is longer and more storied than many realize. Rudimentary versions appeared as early as the late 18th century, often consisting of leather or canvas belts running over flat wooden beds, primarily used for moving sacks of grain onto ships. These early systems were typically powered by hand cranks or simple steam engines. The true revolution, however, began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Thomas Robins, an American inventor, developed a series of innovations around 1892 that are credited with creating the first conveyor system used for carrying heavy, abrasive materials like coal and ore. His work, which included developing a durable rubber belt and the troughed idler design, laid the groundwork for the heavy-duty belt conveyor system we see in mining and bulk material handling today (Goodyear, 1953).

The 20th century witnessed a rapid evolution, driven by industrialization. Henry Ford’s pioneering use of the moving assembly line in 1913, which heavily relied on conveyor systems, demonstrated their power to revolutionize manufacturing. As material science advanced, so did conveyor belts, with the introduction of synthetic fabrics and steel cords that allowed for greater lengths, higher tensions, and increased durability. The latter half of the century and the dawn of the 21st brought automation, with the integration of electric motors, variable speed drives, sensors, and programmable logic controllers (PLCs). By 2025, these systems are no longer just mechanical movers; they are intelligent networks, capable of sorting, weighing, and tracking items in real-time, fully integrated into the broader digital ecosystem of a facility.

Distinguishing a Belt Conveyor System from Other Material Handling Methods

To appreciate the specific genius of the belt conveyor system, it helps to compare it with other forms of material handling. Each method has its place, determined by the nature of the material, the distance of transport, the required throughput, and the complexity of the path.

Consider, for example, a pneumatic conveyor, which uses air pressure to move materials through a pipeline. This is excellent for fine powders or grains over complex, enclosed paths but is generally less energy-efficient for heavy, bulky items. Or think of an overhead crane, which is ideal for lifting extremely heavy, discrete objects within a limited area but cannot provide the continuous flow needed for high-volume operations. Screw conveyors, or augers, are perfect for moving semi-solid materials or grains over short distances, often while mixing them, but they can be abrasive to the material and are not suited for long-distance transport.

The belt conveyor system occupies a unique and versatile niche. It excels at moving a wide variety of materials—from fine powders to large, lumpy rocks, from delicate electronic components to bulk agricultural products. It can be configured to operate over immense distances, with some single-flight systems in mining operations stretching for several kilometers. It is scalable, relatively energy-efficient for the volume it handles, and offers a gentleness of transport that is vital for fragile goods. Its open design allows for easy loading, unloading, and inspection, making it a pragmatic and adaptable choice for countless scenarios.

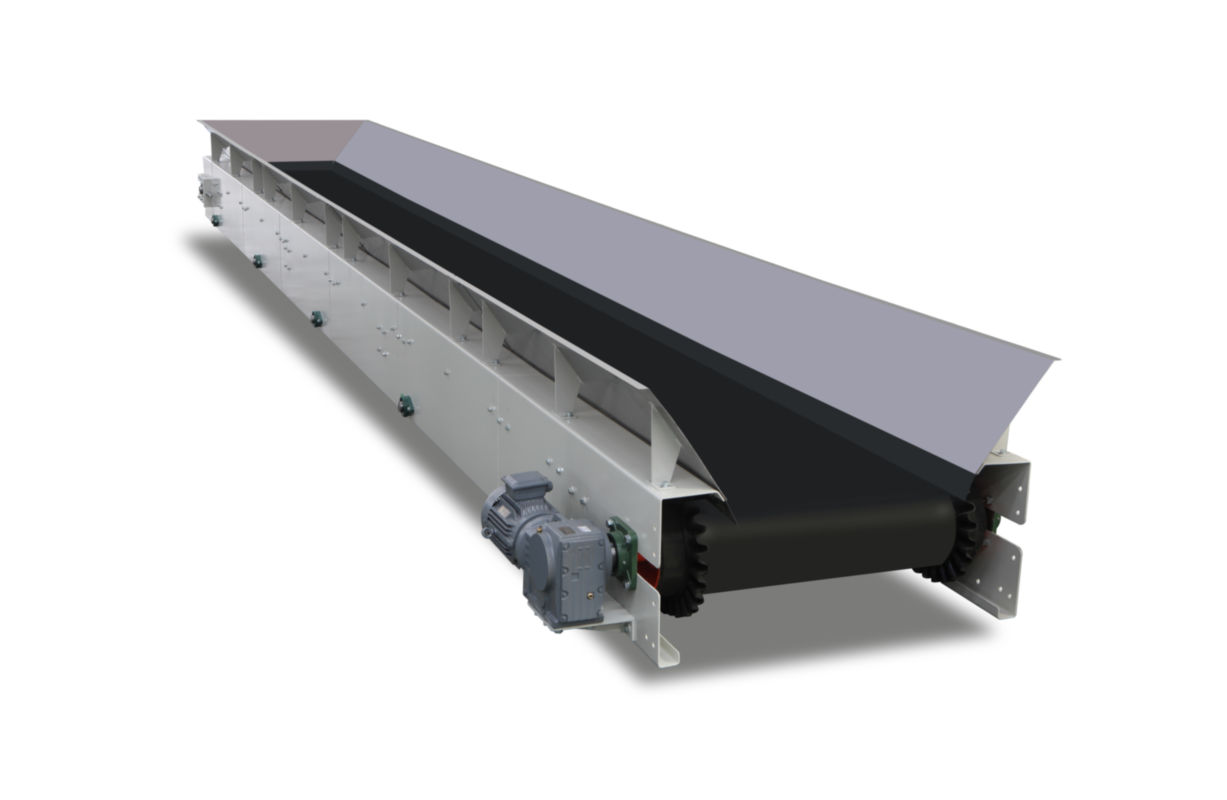

The Anatomy of a Belt Conveyor: Core Components and Their Functions

A belt conveyor system is a symphony of moving parts, where each component must perform its role with precision for the whole to function harmoniously. To understand how to select, operate, and maintain one, we must first become familiar with its anatomy. Let's dissect the system, examining each major component and its contribution to the overall operation.

The Conveyor Belt: The System's Backbone

The conveyor belt itself is the most visible and often the most critical component. It is the surface that carries the load, endures the impacts of loading, and transmits the power from the drive system. The selection of the right belt is a complex decision that hinges on the application.

A conveyor belt is not a simple strip of rubber. It is a composite material, meticulously engineered in layers. The innermost layer is the carcass, which provides the belt's tensile strength and structural integrity. The carcass is typically made of one or more plies of woven fabric (like polyester or nylon) or, for very high-tension applications, steel cords running longitudinally. The number of plies and the type of fabric determine the belt's strength rating.

The carcass is protected by the top and bottom covers, which are usually made of rubber or a synthetic polymer like PVC. The top cover is the load-carrying side and is generally thicker to withstand abrasion, cutting, and impact from the material being conveyed. The bottom cover is thinner, as it primarily contacts the smooth rollers and pulleys. The specific compound used for the covers is chosen based on the application—for instance, oil-resistant compounds are used in food processing, while fire-resistant compounds are required in underground mining.

The surface of the belt can also be specialized. While many are smooth, some applications require textured or cleated surfaces. Cleated belts feature raised partitions perpendicular to the belt's direction of travel. These cleats are indispensable for incline or decline conveyors, as they prevent loose or round materials from rolling or sliding backward.

| Belt Material | Key Properties | Common Industries & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) | Lightweight, resistant to oils and fats, low-stretch. | Food processing, packaging, airport baggage handling. |

| Rubber (SBR, Neoprene) | High durability, excellent abrasion resistance, flexible. | Mining, quarrying, construction (for sand, gravel, coal). |

| Polyurethane (PU) | High strength, cut and tear resistant, non-marking. | Pharmaceutical, electronics assembly, cleanroom environments. |

| Fabric (Cotton, Polyester) | Low cost, good for light-duty applications. | Agriculture (harvesting), retail checkouts. |

| Modular Plastic | Interlocking plastic bricks, easy to repair, can form curves. | Bottling and canning, automotive, food processing. |

| Steel Cord | Extremely high tensile strength, low elongation. | Long-distance overland conveying, heavy-duty mining. |

The Drive System: Powering the Movement

The drive system is the engine of the conveyor, providing the force necessary to move the belt and its load. The primary component is an electric motor, which converts electrical energy into rotational mechanical energy. The size and power of the motor are calculated based on the belt speed, load, incline, and frictional losses of the entire system.

The motor typically does not connect directly to the drive pulley. Its high rotational speed must be reduced to a manageable level suitable for the conveyor. This is the job of the gearbox or speed reducer. The reducer uses a series of gears to decrease the speed while proportionally increasing the torque—the rotational force that actually turns the pulley.

Connecting the motor and the reducer, and the reducer and the drive pulley, are couplings. These components transmit the torque while accommodating slight misalignments between the shafts, absorbing shock loads, and in some cases, providing a point of overload protection. The entire assembly—motor, reducer, and couplings—is known as the drive unit and is almost always located at the discharge end of the conveyor, pulling the belt towards it.

Pulleys: Guiding and Tensioning the Belt

Pulleys are the cylindrical drums that support and guide the conveyor belt, transmit the driving force, and help maintain tension. They are not all the same; different types of pulleys serve distinct functions.

- Drive Pulley: This is the pulley connected to the drive unit. It transmits the power to the belt through friction. To increase this friction and prevent slippage, the drive pulley is often "lagged," meaning its surface is coated with a rubber or ceramic material. It is typically the largest-diameter pulley in the system.

- Tail Pulley: Located at the opposite end of the conveyor from the drive pulley, the tail pulley's primary role is to return the belt. In many simpler systems, it is also part of the take-up unit used for tensioning.

- Snub Pulleys: These smaller pulleys are placed near the drive pulley to increase the "wrap angle" of the belt around the drive pulley. A larger wrap angle means more surface contact, which increases the frictional grip and allows for more efficient power transmission.

- Bend Pulleys: These are used to change the direction of the belt, such as where the belt enters the take-up unit or transitions from an incline to a horizontal path.

- Take-Up Pulley: This is a movable pulley that is part of the tensioning system. By adjusting its position, the overall length of the belt path is changed, thereby increasing or decreasing the belt tension.

Idlers and Rollers: Supporting the Load

If pulleys are the guides at each end, idlers are the supporters all along the way. Idlers are sets of rollers, typically mounted in a frame, that support the weight of the belt and the material it carries. There are two main sections of idlers: those on the top (carrying side) and those on the bottom (return side).

- Troughing Idlers: On the carrying side of a conveyor handling bulk materials, the idlers are arranged to form a trough. A typical setup uses three rollers: a flat central roller and two angled wing rollers. This trough shape centers the load, increases the carrying capacity of the belt, and prevents spillage. The angle of the wing idlers, known as the troughing angle (commonly 20°, 35°, or 45°), is chosen based on the material's properties.

- Impact Idlers: Located directly under the loading point of the conveyor, these idlers are specially designed to absorb the shock of falling material. They are often built with rubber rings or other cushioning materials to prevent damage to the belt and the idler bearings.

- Return Idlers: These are the rollers that support the belt on its return journey underneath the conveyor. They are typically single, flat rollers. In environments with sticky materials, self-cleaning return idlers with a spiral or rubber disc design may be used to prevent material buildup on the belt and rollers.

- Training Idlers: These are specialized idlers that pivot automatically to steer a wandering belt back to the center of the conveyor structure, ensuring proper tracking.

The Frame or Structure: Providing Stability

The frame, or stringer, is the skeleton of the belt conveyor system. It is the structural framework that supports the pulleys, idlers, and drive unit, maintaining their alignment and elevation. The frame can be constructed from formed steel sections or heavy-duty trusses, depending on the length of the conveyor and the weight it must support. For long overland systems, the frame may consist of a series of ground-mounted modules or be elevated on support bents. The design of the frame must account for the static weight of the components and load, as well as dynamic forces from starting, stopping, and material impact.

Tensioning and Take-Up Units: Maintaining Belt Integrity

Proper belt tension is arguably the most important factor for reliable conveyor operation. Insufficient tension will cause the belt to slip on the drive pulley and to sag excessively between idlers, increasing power consumption and material spillage. Excessive tension will place undue stress on the belt, its splices, the pulleys, and the bearings, leading to premature failure.

The take-up unit is the mechanism responsible for applying and maintaining the correct amount of tension. There are several types:

- Manual (Screw) Take-Up: The simplest form, where the tail or take-up pulley is mounted on a sliding frame that can be adjusted with long screws. This is suitable for shorter, less critical conveyors.

- Gravity Take-Up (GTU): This is the most common and reliable method for longer or more heavily loaded conveyors. The take-up pulley is mounted in a vertical carriage that is free to move up and down. A large counterweight is attached to this carriage via cables, applying a constant, predictable tension to the belt regardless of load variations or belt stretch over time.

- Automatic (Hydraulic/Pneumatic) Take-Up: In some advanced systems, hydraulic or pneumatic cylinders are used to position the take-up pulley and apply a controlled tension. These are often integrated with sensors to provide precise tension management.

Understanding these components is the first step toward appreciating the belt conveyor system as a cohesive, dynamic machine. Each part has a purpose, and their successful integration is a testament to decades of refined engineering.

The Physics and Engineering Behind Belt Conveyor Operation

To move from a descriptive understanding to a functional one, we must engage with the physical principles that govern a belt conveyor system. The reliable transport of materials is not a matter of chance; it is the result of a carefully calculated balance of forces. An operator or engineer who comprehends these underlying physics can diagnose problems more effectively, optimize performance, and ensure safe operation. Let's delve into the core engineering concepts.

Understanding Belt Tension: The Heart of Conveyor Dynamics

At any given moment, the tension in a conveyor belt is not uniform throughout its loop. It varies significantly from point to point. The key to understanding this is to think about the forces being applied. The drive pulley pulls the belt. This means the section of the belt approaching the drive pulley (the carrying side) is under high tension, while the section leaving the drive pulley (the return side) is under lower tension.

This tension differential is what makes the system work. Let’s label the tension in the tight side (approaching the drive) as T1 and the tension in the slack side (leaving the drive) as T2. The force available to move the load and overcome friction is the difference between these two, known as the effective tension (Te). Te = T1 – T2

The drive motor must supply this effective tension. However, you cannot simply have T2 be zero. A certain amount of slack-side tension (T2) is required to ensure there is enough grip, or traction, between the belt and the drive pulley. Without sufficient T2, the pulley would just spin without moving the belt, an event known as drive slippage. The relationship that governs this is the Eytelwein or capstan equation, which states that the ratio of the tight-side to slack-side tension is related to the coefficient of friction (μ) between the belt and pulley and the angle of wrap (θ) of the belt around the pulley: T1 / T2 ≤ e^(μθ)

This equation tells us something powerful: we can increase the pulling capacity (the T1/T2 ratio) by either increasing the coefficient of friction (e.g., by lagging the pulley) or by increasing the wrap angle (e.g., by using a snub pulley). The job of the take-up system is to provide the minimum required T2 tension at all times to satisfy this condition and prevent slippage, while also limiting the sag of the belt between idlers.

Calculating Power Requirements: Overcoming Friction and Gravity

Where does the need for power come from? A motor on a belt conveyor system does work against several forces. A simplified power calculation involves summing the forces needed to overcome different types of resistance.

- Friction: This is the largest consumer of power in most horizontal conveyors. It includes the friction of the belt sliding over the idlers, the internal friction of the belt flexing as it moves, and the friction within the idler bearings themselves.

- Gravity: If the conveyor is lifting material up an incline, the motor must work against gravity. The power required is directly proportional to the mass of the material being lifted and the vertical height of the lift. Conversely, on a decline conveyor carrying a heavy load, gravity can actually help move the belt, and the motor may need to act as a brake to control the speed. This is known as a regenerative load.

- Inertia: When the conveyor starts from a standstill, the motor must provide extra power to accelerate the mass of the belt, the pulleys, the idlers, and the material on the belt up to operating speed.

- Material Churning: There is a small amount of energy lost as the material churns and settles while being carried on the belt.

Engineers use detailed formulas, often provided in standards like the Conveyor Equipment Manufacturers Association (CEMA) handbook, to calculate the total effective tension (Te) required to overcome all these forces. Once Te is known, the power (P) required at the drive pulley can be calculated simply by: P = Te × v where 'v' is the belt velocity. This gives the power needed, to which engineers add a safety factor and account for the inefficiencies of the motor and gearbox to select the appropriate drive unit.

The Role of Friction: An Essential Force to Manage

Friction in a belt conveyor system is a double-edged sword. As we saw, the friction between the belt and the drive pulley is essential for transmitting power. We want to maximize this friction. However, the friction between the belt and the idlers, and the internal friction of the components, represents an energy loss that we want to minimize.

Think about this: a long, overland conveyor might have thousands of idler rollers. Even a tiny amount of extra friction in each idler's bearings, when multiplied by the total number of idlers, can lead to a substantial increase in the power required to run the conveyor. This is why the quality of idler bearings and their seals is so important for energy efficiency. Low-friction bearings can significantly reduce the total cost of ownership over the life of the system, especially in regions with high energy costs. This is a primary consideration for operations in Europe, for instance, where energy efficiency standards are stringent.

Tracking and Alignment: Keeping the Belt on Course

A common operational headache is belt mistracking, where the belt drifts to one side of the conveyor structure. If left uncorrected, a mistracking belt can rub against the frame, causing severe damage to the belt edge and the structure itself. It can also lead to material spillage.

What causes mistracking? The belt will always try to move toward the end of the roller or pulley that it contacts first. Therefore, the root cause of mistracking is almost always the misalignment of a component. If an idler or a pulley is not perfectly perpendicular (square) to the direction of travel, it will steer the belt off-center. Other causes can include an unevenly loaded belt, material buildup on rollers, or a poorly made belt splice that is not square.

Proper tracking is achieved through meticulous alignment during installation. All pulleys and idlers must be squared to the frame. For ongoing adjustments, specialized "training" idlers can be used. These idlers pivot on a central pin and can be manually adjusted or are self-aligning, automatically steering the belt back to the center. Achieving and maintaining good belt tracking is a crucial skill for any conveyor technician.

Engaging with these physical principles elevates one's understanding from that of a simple user to an informed operator. It allows for a deeper appreciation of the machine's design and provides the intellectual tools needed for effective troubleshooting and optimization.

A Typology of Belt Conveyor Systems: Matching the Machine to the Mission

The term "belt conveyor system" encompasses a wide family of machines, each adapted for specific tasks, materials, and environments. Choosing the right type is fundamental to achieving operational goals. The selection depends on a nuanced understanding of the material to be handled, the path it must travel, and the required throughput. Let's explore some of the most common types.

| Conveyor Type | Primary Use Case | Key Feature(s) | Typical Industries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flat Belt | Transporting individual items, assembly tasks. | Flat, smooth belt surface. | Manufacturing, Logistics, Food Packaging. |

| Troughing Belt | High-volume bulk material transport. | Belt forms a trough via angled idlers. | Mining, Quarrying, Agriculture (Grains). |

| Cleated Belt | Moving materials up or down inclines. | Raised partitions (cleats) on the belt. | Recycling, Agriculture, Food Processing. |

| Modular Belt | Complex paths, wash-down environments. | Interlocking plastic segments. | Food & Beverage, Automotive, Bottling. |

| Curved Belt | Navigating corners and facility layouts. | Tapered rollers and a specialized belt. | Airports (Baggage), Warehousing, Packaging. |

Flat Belt Conveyors: For Internal Logistics and Assembly

The flat belt conveyor is perhaps the most familiar type, often seen in supermarkets, airports, and factories. As the name suggests, the belt runs flat over a series of rollers or a solid slider bed. Its primary function is to move discrete items with regular shapes, such as boxes, totes, or individual parts.

In a manufacturing setting, such as an electronics plant in Southeast Asia, a series of flat belt conveyors might form an assembly line. Workers can stand alongside the conveyor, performing tasks on components as they move past. The smooth, continuous surface provides a stable mobile workbench. In a logistics warehouse, they are used to transport packages from sorting areas to loading docks. The simplicity, reliability, and low cost of flat belt conveyors make them the workhorse of internal logistics and light-duty manufacturing.

Troughing Belt Conveyors: For Bulk Material Handling

When the task is to move large quantities of loose, bulk materials—like coal from a mine in South Africa, iron ore in Brazil, or grain from a silo in Russia—the troughing belt conveyor is the undisputed champion. This is the design that revolutionized heavy industry.

The key innovation is the use of troughed idlers, which shape the flexible belt into a U-shape or trough. This simple change has two profound effects. First, it dramatically increases the carrying capacity of the belt compared to a flat belt of the same width. Second, the trough shape naturally centers the material, minimizing spillage even at high speeds and over long distances. The depth of the trough is determined by the troughing angle of the idlers, which can be adjusted to suit the "angle of repose" of the material being carried. These are the systems that can stretch for kilometers across rugged terrain, forming the arteries of the world's primary resource industries. When high volume is the goal, troughing belt conveyors are the solution. For those in heavy industry, sourcing a robust bulk material handling conveyor is a critical procurement decision.

Incline/Decline Belt Conveyors: Conquering Vertical Space

In many facilities, materials need to be moved not just horizontally but also vertically, between different floors or elevations. Incline and decline belt conveyors are designed for this purpose. While a standard flat or troughing belt can handle shallow angles, steeper inclines present a challenge: gravity will cause smooth or round items to slide or roll back.

To overcome this, incline conveyors often feature belts with a high-friction or textured surface. For even steeper angles, a cleated belt is used. The cleats act as small barriers, holding the material in place as it moves up the incline. The height, spacing, and shape of the cleats are designed based on the size and nature of the product. These systems are essential in applications like feeding materials into a hopper, moving recycled materials up to a sorter, or transporting packaged goods between mezzanine levels in a warehouse.

Cleated Belt Conveyors: Securing Loose Materials on Slopes

While closely related to incline conveyors, cleated belt systems deserve their own category due to their specialized nature. The design of the cleat itself is a science. Inverted 'V' shapes, 'U' shapes, or straight cleats are chosen depending on the material. For example, when moving fine powders, a 'U' shape might be best to scoop the material, while for lumpy items, a straight, tall cleat might be more effective.

These conveyors are fixtures in the agricultural sector for moving harvested crops, in recycling plants for elevating mixed waste, and in the food industry for transporting items like chopped vegetables or snack foods. The ability to move loose materials at steep angles without slippage allows for much more compact facility layouts, saving valuable floor space.

Modular Belt Conveyors: Versatility and Easy Maintenance

A modular belt conveyor is constructed differently from a conventional belt. Instead of a single, continuous loop of fabric and rubber, the belt is made from countless small, interlocking plastic modules, connected by plastic rods. This construction gives it several unique advantages.

First, it is extremely durable and resistant to cuts and impacts. If a section is damaged, you only need to replace the few affected modules, rather than the entire belt, which significantly reduces maintenance time and cost. Second, because it is positively driven by sprockets that engage with the underside of the belt, there are no issues with tracking or slippage. Third, the open, grid-like structure of some modular belts makes them easy to clean, making them a favorite in the food and beverage industry where hygiene is paramount. Finally, specialized modules allow these conveyors to travel in straight lines, go around curves, and even up inclines, all within a single, continuous system. This versatility makes them ideal for complex paths in bottling plants or automotive sub-assembly lines.

Curved Belt Conveyors: Navigating Complex Layouts

In many facilities, a straight line is not the most efficient path. Curved belt conveyors are designed to transport items around corners, allowing for L-shaped or U-shaped production flows. Achieving this requires clever engineering. The belt itself is often of a standard flat type, but it moves over a bed of tapered rollers. The rollers are wider on the outside of the curve and narrower on the inside. This difference in diameter causes the outer edge of the belt to travel faster than the inner edge, allowing the entire belt to navigate the curve smoothly without buckling or stretching unevenly. These are the systems you see gracefully snaking through airport baggage handling areas or connecting different parts of a complex packaging line.

Each of these conveyor types represents a specific solution to a material handling problem. A thoughtful analysis of the application's needs is the first step in selecting the right tool for the job.

Belt Conveyor Systems in Action: A 2025 Look at 5 Key Industries

The theoretical understanding of a belt conveyor system comes to life when we examine its application in the real world. Across diverse industries and geographic regions, these systems are the unsung heroes of productivity. As of 2025, their integration with modern technology has made them more indispensable than ever. Let's journey through five key sectors to see how they are put to work.

Industry 1: Mining and Quarrying – The Heavy Lifters

In no industry is the raw power and scale of the belt conveyor system more evident than in mining and quarrying. Here, the task is to move millions of tons of abrasive, heavy material, often over vast distances and in harsh conditions. The systems used are titans of engineering.

Consider a large open-pit copper mine in the Andes of South America. The ore is first blasted and loaded by massive shovels into haul trucks. But driving these trucks all the way from the pit floor to the processing plant, often kilometers away and hundreds of meters higher, is inefficient and costly in terms of fuel, labor, and vehicle maintenance. The modern solution is an In-Pit Crushing and Conveying (IPCC) system. Trucks dump their load into a primary crusher located within or at the edge of the pit. The crushed ore, now a manageable size, is fed onto a series of heavy-duty, steel-cord troughing belt conveyors. These overland conveyors, as they are known, form a continuous "river of rock," transporting the ore up steep inclines and across the rugged landscape directly to the processing plant.

These systems are marvels of durability. The belts are thick, with high-tensile steel cords providing the strength to span long distances and carry immense loads. The impact idlers at the loading points are robustly designed to withstand the constant bombardment of rock. The drive systems involve powerful motors and large, lagged pulleys to transmit the immense torque required. In 2025, these conveyors are also intelligent. They are equipped with sensors that monitor belt wear, bearing temperatures, and power consumption in real-time. This predictive maintenance data is fed to a central control room, allowing technicians to address potential failures before they happen, a vital capability in an industry where downtime costs millions of dollars per day.

Industry 2: Manufacturing and Assembly – The Production Pacemakers

In the world of manufacturing, from automotive plants in Europe to electronics factories in Southeast Asia, the belt conveyor system sets the pace of production. Here, the focus is not on raw power but on precision, reliability, and integration.

Picture a car assembly plant in Germany. The bare chassis of a vehicle begins its journey on a specialized conveyor. As it moves down the line, a synchronized flow of components is delivered to the exact point of use by a network of smaller belt and roller conveyors. A flat belt conveyor might bring a sequence of dashboards to the line, while another delivers seats. The speed of these conveyors is precisely controlled and synchronized with the main assembly line. Workers can perform their tasks—installing wiring harnesses, fitting trim—on the vehicle as it moves slowly but steadily forward.

The belts used here are often specialized. They might have non-marking polyurethane surfaces to protect the painted car bodies or be designed to be resistant to the oils and chemicals used in the assembly process. In 2025, these systems are deeply integrated with robotics. A robot arm might pick a component from a moving belt conveyor, identified by a vision system, and install it on the car. The conveyor system acts as the circulatory system of the factory, ensuring that the right part arrives at the right place at the right time, enabling the high-volume, high-quality production that defines modern manufacturing.

Industry 3: Logistics and Warehousing – The E-Commerce Engine

The explosive growth of e-commerce has transformed logistics and warehousing into a high-tech, high-speed industry. At the heart of every large distribution center, from the United States to the Middle East, lies a complex and sprawling network of belt conveyor systems.

Imagine a massive e-commerce fulfillment center in Dubai during a major sales event. An order is placed online. In the warehouse, a worker picks the item from a shelf and places it into a tote. That tote is then placed onto a belt conveyor, where its journey begins. It travels at high speed, merging with other totes, and is scanned by barcode readers. Based on its destination, it is automatically diverted onto different lines using high-speed sorting mechanisms. It might travel up an incline conveyor to a mezzanine level for gift-wrapping, then move along a curved conveyor to a packing station. Once packed into a shipping box, the final package is weighed and labeled in-motion on another belt conveyor before being sorted by destination and sent down a chute to the correct loading dock.

This entire process, handling hundreds of thousands of items per day, is orchestrated by a sophisticated Warehouse Control System (WCS). The belt conveyor system is the physical infrastructure that executes the WCS's commands. The belts are designed for high speed and low noise. The system uses a combination of flat belts, curved belts, and modular belts to navigate the complex layout of the facility, making it a prime example of how industrial belt conveyor systems are the backbone of modern commerce.

Industry 4: Agriculture and Food Processing – From Farm to Table

The journey of food from the field to our plates relies heavily on belt conveyors, which are adapted to handle everything from rugged raw grains to delicate, hygiene-sensitive finished products.

Think of the grain harvest on the vast plains of Russia or Ukraine. Combine harvesters unload tons of wheat into trucks, which then transport it to a grain elevator. Inside the elevator, a series of heavy-duty troughing belt conveyors takes over, moving the grain into storage silos or loading it onto trains or ships for export. These conveyors must be robust, capable of handling high volumes, and designed to minimize dust explosion risks.

Now shift to a fruit processing plant in Thailand. Here, the requirements are completely different. Hygiene is paramount. The belt conveyors used to wash, sort, and transport the fruit are often made of modular plastic or have solid polyurethane belts. These materials are non-porous, easy to clean, and meet strict food safety standards (FDA, EU regulations). The surfaces are smooth to prevent bruising the delicate fruit. Often, these systems are integrated with optical sorting machines. As the fruit travels along the belt, a high-speed camera inspects each piece, and jets of air are used to blow any substandard fruit off the belt into a rejection chute. In this context, the belt conveyor is not just a transporter but a key part of the quality control process.

Industry 5: Waste Management and Recycling – The Sustainability Stream

As the world grapples with sustainability, the waste management and recycling industry has become increasingly sophisticated. Belt conveyor systems are essential for sorting the complex stream of materials we discard.

Step inside a modern Material Recovery Facility (MRF) in a city like Johannesburg, South Africa. A front-end loader dumps a pile of mixed recyclables—plastic bottles, paper, glass, metal cans—into a hopper. This material is then fed onto a series of incline belt conveyors. As the material moves along, it passes through various sorting stations. A large rotating screen might separate cardboard. A powerful magnet suspended over the belt pulls out ferrous metals like steel cans. An eddy current separator, which creates a magnetic field, repels non-ferrous metals like aluminum cans, causing them to jump off the belt into a separate bin.

Further down the line, a combination of human sorters and optical sorters separate different types of plastics. The human sorters stand alongside a wide, slowly moving belt conveyor, picking specific items and dropping them into chutes. The conveyor belts used in this environment must be incredibly tough and cut-resistant to withstand broken glass and sharp metal. Cleated belts are used to move the material up steep inclines between different sorting stages. The entire facility is a dynamic, multi-level maze of conveyors, working to turn our waste back into valuable resources.

Selecting the Right Belt Conveyor System: A Strategic Decision Framework

The acquisition of a belt conveyor system is a significant capital investment. Making the right choice requires a systematic and thorough evaluation of the intended application. A poorly chosen system can lead to operational bottlenecks, high maintenance costs, safety hazards, and a failure to achieve the desired return on investment. To navigate this decision, one must adopt a strategic framework, moving from the material itself to the broader operational and financial context.

Defining Your Material Characteristics: The First Critical Step

Everything begins with the material. The properties of the product you intend to move will dictate nearly every aspect of the conveyor's design. You must ask a series of detailed questions:

- What is the material? Is it a bulk solid, a packaged item, or individual parts?

- What are its physical properties? Consider its size (minimum, maximum, average), shape, and weight. For bulk solids, what is the bulk density (e.g., in kg/m³)? What is its angle of repose and surcharge angle? These angles determine how the material will sit on the belt and are crucial for calculating the capacity of a troughing conveyor.

- What are its characteristics? Is it abrasive, corrosive, oily, or sticky? Is it fragile and requires gentle handling? Is it a food product requiring hygienic surfaces? Is it dusty or does it release fumes? Is it explosive? The answers will guide the selection of the belt material, idler type, and safety features. For example, a highly abrasive material like granite will require a belt with a thick, durable rubber cover, while a food product will necessitate a food-grade PVC or modular plastic belt.

Calculating Throughput and Capacity Requirements

Once the material is understood, the next question is: how much of it do you need to move, and how fast? This is the throughput requirement, typically expressed in tons per hour (for bulk materials) or items per minute (for discrete products).

Capacity (for bulk materials) = Bulk Density × Cross-Sectional Area of Load × Belt Speed

This equation shows that you can achieve a desired capacity by adjusting either the cross-sectional area of the load (which is a function of belt width and troughing angle) or the belt speed. There are trade-offs. A wider, slower belt is often gentler on the material and components but has a higher initial cost. A narrower, faster belt may be cheaper initially but can cause more wear and tear, and may not be suitable for dusty or fragile materials. The optimal combination must be carefully determined. It is always wise to design for a capacity slightly higher than your current peak requirement to account for future growth.

Environmental Considerations: Temperature, Moisture, and Corrosives

The environment in which the conveyor will operate is a critical factor.

- Temperature: Will the system operate in extreme cold, such as an unheated warehouse in Russia, or extreme heat, like an outdoor application in the Middle East? Extreme temperatures affect the flexibility of the belt and the viscosity of bearing lubricants. Special low-temperature rubber compounds or high-temperature belts may be required.

- Moisture: Will the conveyor be exposed to rain, snow, or high humidity? Is it in a wash-down environment, like a food processing plant? Moisture can cause corrosion of the steel frame and bearings. Galvanized or stainless steel frames, along with well-sealed bearings, are necessary in wet conditions.

- Corrosive Elements: The presence of salt, chemicals, or acidic materials in the atmosphere or the product itself will accelerate corrosion. In such cases, stainless steel construction or specialized protective coatings for the frame and components are not a luxury but a necessity.

Safety, Regulation, and Compliance Across Regions

Safety is not negotiable. Belt conveyor systems have inherent hazards, including pinch points at pulleys and idlers, and the risk of entanglement with the moving belt. The design must incorporate safety features mandated by regional and international standards, such as OSHA in the United States, CE marking requirements in Europe, and other national regulations.

Essential safety features include:

- Guarding: All drive components, pulleys, and accessible pinch points must be fully guarded.

- Emergency Stops: Pull-cord switches running the length of the conveyor and push-button emergency stops at operator stations are mandatory. These must be designed to immediately cut power to the drive motor.

- Warning Labels: Clear and universally understood warning labels should be placed at all hazard points.

- Lockout/Tagout Provisions: The motor control system must have a clear and robust procedure for de-energizing and locking out the power source before any maintenance is performed.

Compliance with these standards is not only a legal requirement but also a moral one, ensuring the well-being of all personnel who interact with the equipment.

Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) vs. Initial Investment

A common mistake is to select a conveyor based solely on the lowest initial purchase price. A more astute approach considers the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) over the system's entire life cycle. TCO includes:

- Initial Purchase Price (Capex): The cost of the equipment itself.

- Installation Costs: The labor and resources required to install and commission the system.

- Operating Costs (Opex): This is a major component and includes the cost of energy to run the conveyor, the cost of labor to operate it, and the cost of routine maintenance.

- Maintenance and Repair Costs: The cost of replacement parts (belts, idlers, bearings) and the labor to install them.

- Downtime Costs: The cost of lost production when the conveyor is out of service. This is often the largest and most overlooked cost.

A slightly more expensive conveyor with higher quality components—such as premium bearings, a more durable belt, and a more efficient drive system—may have a significantly lower TCO. It will consume less energy, require fewer replacement parts, and experience less unplanned downtime. When evaluating proposals from vendors, it is crucial to look beyond the initial price tag and assess the long-term value and reliability offered by the proposed design.

The Future of Belt Conveyors: Innovations and Trends for 2025 and Beyond

The belt conveyor system, despite its long history, is far from a static technology. It is continuously evolving, driven by advances in materials science, digital technology, and a growing emphasis on sustainability and safety. As we look to the future from our vantage point in 2025, several key trends are shaping the next generation of conveying.

The Rise of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) and Predictive Maintenance

The most significant transformation is the integration of smart sensors and connectivity—the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). The conveyor is no longer an isolated piece of machinery but a data-generating asset.

- Condition Monitoring: Sensors are being embedded throughout the system. Acoustic sensors listen to the sound of idler bearings to detect early signs of wear before they fail. Temperature sensors monitor motors and gearboxes for overheating. Vibration analysis can predict misalignments or imbalances.

- Belt Health Monitoring: Advanced systems now use embedded sensors or optical scanning to monitor the condition of the conveyor belt itself. They can detect rips, tears, and excessive wear, and even measure the thickness of the cover in real-time.

- Predictive Maintenance: All this data is fed into a cloud-based platform or a local control system. Using machine learning algorithms, the system can move beyond simple alerts to predictive analytics. It can forecast when a component is likely to fail, allowing maintenance to be scheduled proactively during planned shutdowns. This shift from reactive (fixing what's broken) or preventive (maintenance on a fixed schedule) to predictive maintenance dramatically reduces unplanned downtime and lowers maintenance costs.

Energy Efficiency and Sustainable Conveying

With rising energy costs and a global focus on sustainability, reducing the power consumption of conveyor systems is a major priority.

- High-Efficiency Drives: Modern drive systems use premium-efficiency motors and variable frequency drives (VFDs). VFDs allow the speed of the conveyor to be precisely matched to the required throughput, so the system only uses the energy it needs. During periods of low demand, the belt can be slowed down, generating significant energy savings.

- Low-Resistance Components: There is a major focus on developing idler rollers with very low rolling resistance. This involves advanced bearing designs, superior sealing systems to keep out contaminants, and lightweight composite materials for the rollers themselves. Reducing the friction of each of the thousands of idlers on a long conveyor can result in a substantial reduction in overall power consumption.

- Regenerative Braking: On long, downhill (decline) conveyors, the force of gravity acting on the load can be so great that it drives the belt, and the motor must act as a brake to control the speed. In modern systems, this braking action is used to generate electricity, which can be fed back into the facility's power grid. This turns a potential energy waste into a source of power.

Advancements in Belt Materials and Sensor Technology

The conveyor belt itself continues to evolve. Material scientists are developing new rubber and polymer compounds that offer superior resistance to abrasion, cutting, heat, and oil. These new materials extend the life of the belt, which is often the single most expensive component to replace.

The development of lighter, more durable carcass materials allows for belts that are stronger yet require less energy to move. The integration of fiber-optic strands within the belt is another exciting innovation. These fibers can detect stress, strain, and impact along the entire length of the belt, providing an unprecedented level of real-time health monitoring.

Automation, Robotics, and System Integration

Belt conveyors are becoming more deeply integrated with other automated systems. The synergy between conveyors and robotics is particularly powerful. In logistics and manufacturing, it is now common to see robotic arms picking items directly from a moving conveyor belt. This requires sophisticated vision systems to identify and locate the items and precise coordination between the robot controller and the conveyor's drive system.

In bulk material handling, automated systems can control the loading of the conveyor to ensure an even, centered flow, maximizing capacity and preventing spillage. Automated plow systems can be used to discharge material from the belt at multiple, programmable locations. This level of automation reduces the need for manual intervention, improving safety and operational consistency.

The belt conveyor of the future is smarter, more efficient, more reliable, and more integrated than ever before. It is evolving from a simple material mover into a key component of the intelligent, automated facilities of the 21st century.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the primary purpose of a belt conveyor system?

A belt conveyor system's primary purpose is to automate the transport of materials, goods, or bulk solids from one location to another. It provides a continuous flow, which increases efficiency, reduces manual labor, and streamlines production or logistics processes in a wide range of industries.

How do you determine the right speed for a conveyor belt?

The right belt speed is a balance between several factors. It must be fast enough to meet the required throughput (e.g., tons per hour or items per minute) but slow enough to prevent damage to the material, avoid excessive wear on components, and minimize spillage or dust creation. The optimal speed is calculated based on material characteristics, belt width, and capacity goals.

What are the most common causes of conveyor belt damage?

The most common causes of damage are mistracking (where the belt rubs against the structure), impact damage at loading points from falling material, and general abrasion and wear from the material being transported. Material getting trapped between the belt and a pulley can also cause significant damage.

How often should a belt conveyor system be inspected?

Inspection frequency depends on the intensity of use and the criticality of the system. A general best practice is to have operators perform a brief visual inspection at the start of each shift. A more detailed mechanical and electrical inspection by trained maintenance personnel should be conducted on a weekly or monthly basis, with a comprehensive annual inspection.

What is the difference between a troughing idler and a flat return idler?

A troughing idler is located on the top, or carrying side, of the conveyor and consists of multiple rollers (typically three) angled to form a trough in the belt. This shape increases carrying capacity and contains bulk materials. A flat return idler is located on the underside of the conveyor and is usually a single roller that simply supports the flat, empty belt on its return journey.

Can a belt conveyor move items up a steep hill?

Yes, but it requires a specialized design. For steep inclines, standard belts would allow items to slide back down. To prevent this, incline conveyors use belts with a high-friction surface or, for steeper angles, cleats. Cleats are raised profiles on the belt surface that hold the material in place as it moves uphill.

What are the main safety hazards associated with belt conveyors?

The main hazards are mechanical. Pinch points where the belt meets pulleys and idlers can cause severe injuries. There is also a risk of clothing or limbs being caught and pulled in by the moving belt. Electrical hazards exist with the drive and control systems. Proper guarding, emergency stop systems, and lockout/tagout procedures are essential for safe operation.

Conclusion

The belt conveyor system, in its many forms, stands as a testament to the power of elegant engineering. From its rudimentary beginnings to its current status as a sophisticated, intelligent network, its core principle—continuous, efficient movement—has remained a constant driver of industrial progress. We have journeyed through its fundamental mechanics, dissected its anatomical components, and explored the physical laws that govern its operation. We have seen its versatility in action across the globe, from the immense scale of South American mines and the precision of European factories to the high-speed logistics of Middle Eastern distribution centers and the vital food and recycling streams of Africa and Asia.

As we stand in 2025, it is clear that the belt conveyor is not a relic of the industrial past but a dynamic and evolving technology crucial for the future. The integration of IoT, the relentless pursuit of energy efficiency, and advancements in material science are redefining what these systems can achieve. For any professional in the fields of engineering, manufacturing, logistics, or resource extraction, a deep and nuanced understanding of the belt conveyor system is not merely beneficial; it is foundational. It is the key to unlocking greater productivity, ensuring a safer workplace, and building more sustainable operations for the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

References

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company. (1953). Handbook of belting. The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company.

Lodewijks, G. (2011). The next generation of belt conveyor technology. In Belt conveying in the minerals industry conference (pp. 1-14). The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy.

Munzenberger, P., & Wheeler, C. (2016). Belt conveyor roller resistance – A review of CEMA 5 and the current state of knowledge. Bulk Solids Handling, 36(4), 38-46. https://www.bulk-solids-handling.com/media/issues/2016/04/bsh-2016-4-munzenberger-wheeler.pdf

Conveyor Equipment Manufacturers Association. (2014). Belt conveyors for bulk materials (7th ed.). CEMA.

Qiu, X., & Feng, D. (2021). Research on dynamic characteristics of belt conveyor based on flexible multibody dynamics. Shock and Vibration, 2021, 1-13.

Golosinski, T. S. (2001). Environmentally friendly belt conveying. In Proceedings of the 17th international mining congress and exhibition of Turkey-IMCET (pp. 43-49). UCTEA Chamber of Mining Engineers of Turkey. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237337775_Environmentally_Friendly_Belt_Conveying

Zhang, S., & Xia, X. (2011). Modeling and energy efficiency optimization of belt conveyors. Applied Energy, 88(9), 3061-3071.

Zamiralova, M. E., & Lodewijks, G. (2015). Belt conveyor technology: Current status and future trends. FME Transactions, 43(1), 63-71.